Football Community Mourns The Larger-Than-Life Personality Of Bednarik

By David Coulson

Executive Editor

College Sports Journal

PHILADELPHIA, PA. — On my first trip to historic Franklin Field, on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, I made a bit of a pilgrimage.

I walked inside of the 10-yard line to the area of the field where Chuck Bednarik had made the final-play tackle on Green Bay Packers fullback Jim Taylor at the nine-yard line, lifting the Philadelphia Eagles to the 1960 NFL Championship.

I lingered there for several minutes, soaking in the history of a moment that the Eagles still haven’t repeated in the 54 NFL seasons since then.

Bednarik, one of the toughest players ever to strap on a helmet and pads, passed away Saturday morning at the age of 89 after several years of failing health, family sources said.

He died of natural causes at an assisted living facility in Richland, Pa., where he had been admitted on Friday.

Even into his 80s, Bednarik was a no-holds-barred, unapologetic, larger-than-life personality.

The first time we met, he greeted me with one of the firmest handshakes I had ever received, his fingers gnarled by years as a linebacker and center and his non-football career selling concrete.

That off-season job, combined with his aggressive approach to football, earned him the nickname “Concrete Charlie” and served as the title of his biography, written with his beloved son-in-law, Ken Safrowic and Eli Kowalski in 2009.

I left the old Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society in Hatboro, PA. that afternoon with a signed copy of his book and a truckload of memorable stories.

We crossed paths several years later at Franklin Field when he was honored by his alma mater with the dedication of a beautiful bronze statue that resides in one of the concourses at the stadium where so much of his college and professional career unfolded.

He was a little bit more frail, and walked slower on his battle-scarred legs, but still could welcome you with that death-grip of a handshake.

On that special day, Bednarik was as humorous and irascible as ever.

One of his typical lines:

“In Heaven, there is no beer, that’s why I drink it here.”

A large crowd of friends and former teammates showed up to honor Bednarik.

“Before I leave this world it is nice to see fellows you played in high school and college here,” said Bednarik, reflective even then that his life was nearing its end. “I was proud to have played here.”

Looking at the stately bronze as it was unveiled, this rough and tumble former football star grew slightly misty-eyed.

It’s a big honor for me to have a statue,” said Bednarik. “Growing up, I would have never dreamed of something like this,” adding that the depiction was “magnificent.”

Among the people that showed up that day to honor Bednarik was former Philadelphia Eagles coach Dick Vermeil.

The charismatic Vermeil boiled down this respected pro and college football hall of famed in a few concise sentences.

“Chuck Bednarik is a great American, a great symbol for all of us to recognize what were all made of, or what we wished we were made of,” said Vermeil. “He is just a great symbol of what this area can produce. He is a winner and this is a city of winners. He represented what we wanted to represent.”

Bednarik was the last of the true two-way players in the NFL.

Ironically, ESPN published an obituary on Saturday morning, claiming that Bednarik was the last two-way starter until Deion Sanders — a characteristic that would have had this proud ex-player steaming.

Sanders was the type of modern player than Bednarik loathed.

“The positions I played, every play, I was making contact, not like that … Deion Sanders,” Bednarik was quoted as saying in the ESPN obit. “He couldn’t tackle my wife. He’s back there dancing out there instead of hitting.”

There were few topics a reporter could throw at Bednarik without getting a colorful comment.

When this hard-tackling star heard that television personality Kathie Lee Gifford had criticized his iconic, concussion-causing hit on her husband Frank Gifford years after that play had clinched a key 17-10 victory over the New York Giants to clinch Philadelphia’s berth in the 1960 NFL championship game, Bednarik reacted with a politically-incorrect response.

“I’d punch Kathie Lee Gifford in the face, if I met her,” Bednarik claimed.

Frank Gifford was more respectful of Bednarik’s fumble-causing blow that left the standout running back prone on his back and unconscious with a brain injury so severe that Gifford didn’t return to the Giants until the 1962 season.

It was diagnosed as a spinal concussion years later when an X-ray revealed that Frank Gifford had suffered a broken neck vertebra that healed itself.

“Chuck hit me exactly the way I would have hit him,” Gifford told New York Times columnist Dave Anderson before the 50th anniversary of that game. “With his shoulder, a clean shot.”

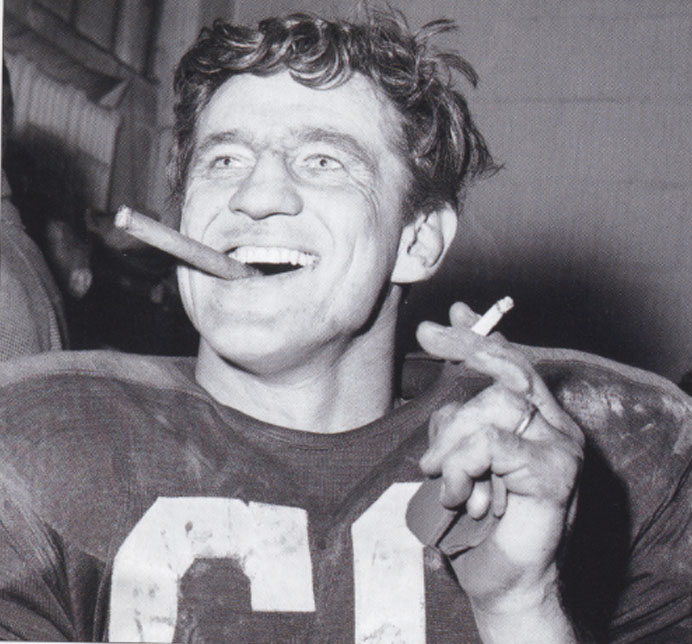

The Sports Illustrated photo captured by John G. Zimmerman of Bednarik celebrating over Gifford’s still body remains one of the most famous images ever snapped in an NFL game.

“I didn’t even notice him laying on the ground,” Bednarik explained. “I was celebrating that one of my teammates (Chuck Weber) had recovered the fumble and we had won the game.”

While the Gifford tackle was the most celebrated of his career, Bednarik’s hard-swagger style had been developed all the way back at Broughal Junior High in his hometown of Bethlehem, PA.

But first, Bednarik had to convince his mother to allow him to play.

“She wouldn’t let me play football,” he said in the recently released book, Concrete Charlie, An Oral History of Philadelphia’s Greatest Football Legend Chuck Bednarik. “She said she didn’t want anyone hurting me.”

Bednarik finally subverted his mother’s concerns by getting his father, Charles, to sign the permission form allowing him to begin his historic career.

He emerged as a football, basketball and baseball star at Bethlehem Technical High School and Liberty High School from 1940-43, before answering the patriotic call of his country when World War II broke out when he was 18.

Bednarik served with the 467th Bomb Group in the Eighth Air Force, flying 30 missions over Germany in a B-24 Liberation Bomber and was decorated with the Air Medal, with four Oak Leaf Clusters, and the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Ribbon, with five Battle Stars.

“You’re only 19 years old and you’re dealing with being shot at,” Bednarik said. “I kissed the ground after my 30th mission.”

Upon his return from battle, Bednarik took advantage of the GI bill to enroll at Penn and play for legendary coach George Munger.

Under Munger’s tutelage, Bednarik developed into one of the top players in the country as a center and linebacker. He also occasionally served as the Quakers’ punter.

“What I remember is 78,000 people coming to our games,” Bednarik said of an era when Penn routinely played some of the top teams in the country and was frequently ranked in the wire-service polls.

The two-time All-American finished third in the voting for the Heisman Trophy in 1948 behind Doak Walker and Charlie “Choo-Choo” Justice, while winning the Maxwell Trophy that same year. The Maxwell Award now honors the college football defensive player of the year with the Chuck Bednarik Award.

When the NFL held its college draft following his senior year, Bednarik was the first overall pick of the Philadelphia Eagles, starting a 14-year pro career that included 10 All-Pro seasons, NFL championships in 1949 and 1960 and induction into the NFL Hall of Fame in 1967.

Two years later, the College Football Hall of Fame also honored the 6-foot-3, 235-pound ironman as one of the all-time greats.

“Players today are over-paid and under-played,” said Bednarik. “I think if you asked them, the players of today would love to get out there and play both ways like I did.”

The 1953 Pro Bowl MVP was named to the NFL’s 50th and 75th anniversary teams and was selected as a member of the league’s all-decade team for the 1950s.

Bednarik made the Philadelphia Eagles Hall of Fame in its first induction class of 1987 and had his uniform number 60 retired by the team.

He endured a highly publicized feud with current Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie, but put those sentiments aside to appear at the Eagles’ training camp at Lehigh University in 2006 and at Lincoln Financial Field in 2010 for the 50th anniversary of Philadelphia’s last NFL title.

Lurie put aside differences to release a statement about Bednarik’s value to the team on the official Philadelphia Eagles website on Saturday.

“With the passing of Chuck Bednarik, the Eagles and our fans have lost a legend. Philadelphia fans grow up expecting toughness, all-out effort and a workmanlike attitude from this team and so much of that image has its roots in the way Chuck played the game. He was a Hall of Famer, a champion and an all-time Eagle. Our thoughts are with his family and loved ones during this time.”

Bednarik, who lived in retirement in Coopersburg, PA., was also a pioneer of what is now the Football Championship Subdivision, sneaking into games at Lehigh’s Taylor Stadium as a youngster before moving on to Penn for college.

“Chuck transcends generations,” said Vermeil, who used his fundraising abilities to help fund that bronze statue that now sits so proudly at Franklin Field. “I hope the University of Pennsylvania makes sure no one ever forgets him. He is a symbol of the university that no one else will ever match.”

This is one writer who will always remember the engaging character and the sparkling, blue eyes and smile that Bednarik carried throughout his remarkable life.