I Used To Watch The NCAA Tournament

This year marked the first year since forever that the NCAA Men’s Basketball tournament wasn’t a big thing for me.

For me that’s a very odd thing, since I’ve always had an interest in the basketball tournament my entire life.

When I was young, the NCAA Tournament was a growing phenomenon – a place where Patrick Ewing and Michael Jordan were first unveiled, and Ralph Samson and Hakeem Olajuwon, and also Dereck Whittenberg and Ed Pinckney.

I was blessed to have been born in the age when the NCAA Tournament was a varying mix of schools and some budding college stars were emerging that would end up being NBA superstars, which made the tournament crackle with excitement. For most people, like me, it was their first introduction to these great players.

It was the time when I first became aware of schools like Georgetown, Villanova and North Carolina, and North Carolina State. It’s also when I was introduced to Bobby Knight, Lefty Dreisell, and Pete Carril, coaches with outsized personalities who grafted their unique playing styles onto the teams they coached.

My father loved the NCAA Tournament when I was younger, too. He remembered the great college players of his day, too.

A Dartmouth man, he had memories of the Big Green team that went to the NCAA Tournament while he was an undergraduate, but that was during a time when the NCAA Tournament was obscure, played nationally at a time when televised sports were not common.

There was no concept of March Madness then – the first round took place in New York City, and the Ivy League Champions were trounced by a West Virginia team 82-68 that would feature a dominant future NBA hall-of-famer, Jerry West. Unless they had made the trek to New York City to attend in person, they read about it in the paper the next day,. The privately-run NIT was arguably a bigger tournament at that time.

For me, as a kid, the NCAA Tournament felt different than it does today, probably in similar ways to how it felt different for my father.

It felt like a mass media event. like the Super Bowl or the World Series – a universal gathering of a myriad of different styles of play. Unlike the NBA, which outlawed different zone defenses, each college team had to use their strengths and hide their weaknesses using defenses and drawn up plays in order to prevail. It was one of the many interesting selling points to fans during that time.

March Madness’ overall success came due to an alignment of different factors.

Its place on the calendar, safely nestled in between the end of the Super Bowl and before baseball’s Opening Day, was perfect.

CBS also discovered how to broadcast the tournament in a compelling way. They had the distribution – presence on both cable and a regular antenna over-the-air, as was the custom of the major networks at the time. Everyone in America could watch at the same time without paying for it, and the number of available channels and entertainment options were limited.

By 1985, March Madness’ success on TV was evident, and the NCAA responded by expanding the field to a 64 team bracket. (That year, unbeknownst to me, Lehigh University would become the first team in NCAA history to qualify to play in the NCAA Tournament with a losing record. Behind the blossoming of Darren Queenan and Mike Polaha, they earned the right to be the 16 seed to Georgetown’s 1 seed, which the Championship-bound Hoyas would win comfortably.)

That opened up access to the so-called “mid-major” schools to secure autobids to the tournament – schools like Lehigh, who were at the time in the ECC, or East Coast Conference. It also opened up the floodgates to the unbelievable drama of the first-round upset involving a very low seed- or a close upset. When Pete Carril’s 16th-seeded Princeton team on a casual Friday afternoon had the winning shot in the air at the buzzer against No. 1 seeded Georgetown – only to bounce out of the tight rim – the NCAA Tournament changed forever. Carril forced the Hoyas to not play their game and to be sucked into his slowed-down, deliberate maze of elaborate passing and backdoor cuts, and provided the blueprint to every team that followed that showed that upsets are possible.

In retrospect, those years feel like a golden age. Now, however, things feel different. Too different. So different, in fact, if my alma mater’s not in it, I’m simply no longer interested in watching. That wasn’t the experience of my father.

Gambling

It’s certain that my recollection of these “good old days” of the NCAA Tournament are a bit shinier due to the passage of time.

When I first entered the working world, March meant the yearly office bracket, which involved spending some money to try to pick the winner over the rest of my friends and co-workers.

Picking the winner of the tournament, or out-foxing your co-workers by picking a huge upset like 15th seeded Lehigh to beat 2nd seeded Duke, was a great ego boost. (And when you attended Lehigh men’s basketball games on a regular basis, talked to their star player and actually attended Lehigh, it was a hundred times better.)

While the office pool does fall under the purview of putting money down on the outcomes of sporting events and winning a prize as a result, it never felt like gambling in the traditional sense of putting down money on actual single game bets, worrying about point spreads or parlays. It was fun to try to predict the entire tournament before the first tip-off, and the possibility of winning the lottery – the odds of picking a perfect bracket are steeper than winning the Powerball – was thrilling.

Behind CBS’ compelling stories and theater, however, the dark side of the sport was certainly there to see if you looked for it.

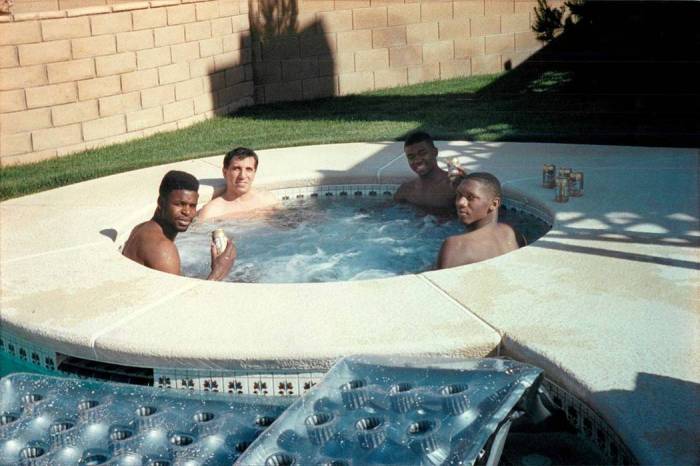

When three of five players on Jerry Tarkanian’s UNLV team were photographed in the hot tub of “convicted sports fixer” Richard Perry, it should have been a bigger deal. Tarkanian should have been banned from coaching in college as a result, but he wasn’t.

When North Carolina State was put on NCAA probation late in Jim Valvano’s career due to the involvement of Charles Shackleford and three Wolfpack players accepting bribes for point shaving, it should have been a bigger deal. Valvano’s later career as a broadcaster and his charitable work before his untimely death to cancer made much of the country forget, but I never fully accepted the idea that he didn’t know what was going on.

In the olden days, when sports bets were only legal in Nevada, there were lots of illegal books and bookies all over the country, many run by organized crime. A small number of these collectives of gamblers would break the law to attempt to pay off college players to not necessarily lose games, but to only win them within the point spreads. For example, a pass to the opposing team ending in a layup could make the margin of victory 8 points instead of 10 points. “Shaving” two points off the winning margin pays off the bettors taking the losing team +8 1/2 points which was what Charles Shackleford and three NC State players were accused of doing.

The practice was not new. CCNY and schools like Seton Hall in the 1950s were involved in the same racket, but it never really stopped, with scandals from Boston College in the 1970s (involving Henry Hill, the mobster fictionalized in Goodfellas) to Tulane in the 1980s. To me, if nothing else, it showed how important it was to keep the competitions pure and to prevent gambling interests from getting at all involved with the sport.

Even as I kept enjoying March Madness in the 90s and 2000s, there were more and more growing signs that the sport was somewhat less than pure. What was shocking was that it wasn’t just a few athletes tempted to shave points for mob money. During this era, more of the cheating was institutional in nature.

Like when the wider world learned North Carolina’s men’s basketball players accounted for 35 bogus classes during the Tar Heels’ 2004-05 national championship season in order to keep them eligible.

Not only did star guard Rashad McCants not have to go to class – he received four A- for simply handing in papers that were written by a tutor – according to Rashad, head coach Roy Williams and the rest of the athletic department were aware of the academic fraud and worked with the students to “keep them eligible”.

The inability of the NCAA to give North Carolina the death penalty for this blatant violation of educational ethics is one of the most astounding things I’ve ever witnessed. Not only did Roy Williams skid athletes through the University of North Carolina, he actually put into question every North Carolina degree issued during that time because his fraud classes were available to all students.

I don’t totally blame the NCAA, unlike many. The NCAA has operated for years in a place where they have very specific powers, but they unfortunately are not built to deal with a fraud that is so vast and so pervasive that it involves the delivery of education to the entire school. As we learned, if a school wants to defraud its students in order to primarily benefit athletics, it can, as long as it defrauds its students equally.

More and more we’ve learned that our state and federal governments are not up to the task of policing and punishing fraud in colleges in general, and especially when it involves beloved State U. Either America can empower the NCAA to do it, the federal government to do it, or the courts will inefficiently do it. In that sense, the case against North Carolina was more of a hint of the dysfunction of all American governance – an obvious fraud with obvious perpetrators that were unpunished.

Somewhere along the way, because we liked March Madness and wanted to believe in clean athletics, we thought of Jerry Tarkanian and Roy Williams as rapscallions, sort-of used car salesmen who bent the rules but had a heart of gold, or something like that.

We didn’t think of who they actually were – cheating frauds who were trying to get around academic rules involving kids’ educations in order to not have a level playing field on the court. Worse, they were frauds that exploited kids by sacrificing their educations in order to give them titles. For the cheated athletes and students, the repercussions last a lifetime while they retire with millions off of their backs. I will never accept a UNC degree from those years as legitimate.

Broken For Good?

Yet for years I still watched.

I still filled out my NCAA brackets and put them in the office pool, my $20 a year lottery ticket.

I watched UMBC and Norfolk State and St. Peter’s and Florida-Gulf Coast and Mercer and thrilled in the upsets and loved watching the blue bloods burn. Watching John Calipari lose to a double-digit seed was the best, even if I didn’t pick them to lose.

There were undeniable great moments. More upsets of Duke and Syracuse. Bill Self losing to a double-digit seed that spent a fraction of what Kansas spends on athletics. Butler’s and George Mason’s improbable runs to the Final Four. St Peter’s to the Sweet 16. They were amazing.

But it’s this year, 2024, where things really feel like they’re broken for good.

Why? Why now?

Certainly part of the problem is gambling has become so ubiquitous and tangled up in all organized sports, including college basketball.

Every sporting event on ESPN now has odds and live betting baked into their broadcasts. ESPN even has its own branded national sportsbook.

In such a landscape, folks in the office space are a lot less interested in playing that $20 pool when they’re plunking $200 in bets down on their phone every week.

At one time, the NCAA Bracket was one of maybe a few times a year when many, many people put a little money down for something sports-related. Now, the NCAA Tournament feels like just another parlay opportunity for hardcore gamblers in a neverending spiral of betting opportunities.

It’s possible that the spread of normalized gambling really started during COVID, and has just continued to grow as the virus has receded. But it has ruined the simpler pleasures of the bracket for everyone.

It’s not just gambling, though.

The college sports landscape, with unlimited transfers and collectives bribing players to induce them to attend their school, have also fundamentally wrecked the tournament for me.

Gone are the days of seeing Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing for several years at a school to see them develop as athletes. As flawed as the system was, at least there was some consistency from year to year and there were expectations.

Every college basketball fan in 1984 was aware of Patrick Ewing and the Hoyas in October, because of what he had done previously in the Big East and the NCAA Tournament. CBS could hype a mid-January game between the Hoyas and Boston College because the wider world of people had seen him at a bare minimum the prior year.

Nowadays, teams hardly stay together more than a year as players try to test the size of the inducements they might get in the “open market”. This season alone, James Madison and Appalachian State have seen almost their entire team enter the transfer portal to test what inducements they might be able to get to lure them away from the educational experiences they had in Harrisonburg and Boone.

It’s bad on so many levels. It’s bad for team cohesion. It’s horrible for all the low- and mid-majors that see talent they’ve identified early, and then developed and cultivate success – then leave for nothing.

And frankly it’s bad for all fans of the sport, casual or hardcore, who need to check their phones every fall to figure out the turnover on the roster. Right now there is no way to think about a team who makes a run in the tournament as “wait until next year, when their freshman improve in the “offseason”. The only thing that matters is the one moment. Once the run ends, the dismantling begins.

As of this moment, James Madison fans have no idea who will be suiting up for them on the hardcourt in October. At no time in history has rooting for a school felt more like rooting for laundry.

I also see the corrupting influence of college athletes’ name, image and likeness payments on the tournament itself.

The wild west of NIL, which has as its father Brett Kavanaugh, is a topic well beyond this one retrospective on the NCAA Tournament. But too little has been made of how NIL affects the competition itself.

The NCAA Tournament takes hitherto unknown student-athletes and make them stars. This year, Jack Gohlke, who out of nowhere sank ten 3 pointers to help Oakland (MI) upset Kentucky, was this year’s Doug Edert. (Remember him?) It’s undeniably a huge part of what makes the tournament great. I too stopped everything and tuned in when it looked like Oakland was about to make history.

But almost as soon as Oakland finished celebrating, vultures were trying to get in trying to monetize Gohlke’s viral moment with merch and a quickly-assembled video for TurboTax.

In a way I enjoy Gohlke’s newfound celebrity – a 5th year senior who probably wouldn’t have sniffed the NBA – but how can such a distracting environment be good for the team as preparations continue to play further in the tournament?

I couldn’t get that out of my head as I watched Gohlke’s performance down the stretch in overtime versus NC State, where the magic of those 3 pointers ran out as he missed the shots that could have propelled them to the Sweet 16.

Say what you want about the fairness of players like Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing not having these “branding” opportunities in college, but the truth you can’t deny is that without them, all the athletes had to do was concentrate on their games during the tournament and classes during the rest of the calendar year. There were no vultures at Campus Ink trying to contact them, no opposing assistant coaches, collectives or NIL lawyers inducing them or confronting them on making portal decisions.

I am not totally against the players getting some part of the broadcast revenue they are generating for the school, the conference and the NCAA. After all, the amounts of money paid to broadcast the games by ESPN, Fox, CBS and NBC is ludicrous. But unregulated NIL is such a distraction and messes up priorities for college students who people forget are still in the arena, needing to compete in 48 hours on the stage of their lives. People treating the kids like brands, not actual human beings.

All of these distractions lead to one path – the product on the court being worse. Gone are the great coaches, because they aren’t coaches anymore, they’re middle managers trying to cajole people into staying in the program and possibly consulting kids on NIL. Gone are great systems, because the sport has devolved into a mini-NBA with no time for funky systems or styles. And soon, the fans will go, too, because there is no link between guns for hire and actual attendees the school that is your alma mater that actually go to class. It’s just a matter of time.

I’m Out For Now

It definitely wasn’t pure, but it sure was simpler, and more to the point, I knew when I saw Ewing and Jordan in the NCAAs I knew I was seeing future greatness, without gambling or branding or distractions affecting the outcomes.

But it’s impossible for me to unsee those things in the game today. With every tweet and every ad showing a college athlete hawking crypto or some phony energy drink, I think a little of everyone’s soul is taken away. I hate ads in general.

So as long as Lehigh isn’t a participant, I just don’t feel like NCAA basketball is something I want to engage with. In so many ways to me it feels broken beyond recognition from the game I grew up watching.

I can’t follow a sport where the school colors are just laundry and each team is just a collection of paid athletes whose inducements are the biggest. I’m not going to watch a sport that breaks down its worth with return on investment and prop bets. I’m just not interested.

The NCAA and commissioners of the big money conference might not care. They might not see. They might be simply thinking of the sport as a cash cow, and looking at yesterday’s ginned-up TV ratings as evidence that the sport is healthy and will keep paying them billions. Like a venture capitalist or a TV executive, they only see the value in the now, not the long term investment in the sport.

But I don’t think I’m alone. And if I’m right, the end result might be a long slide to unsustainable irrelevance to anyone but degenerate gamblers – unless someone convinces them to fix the corruption.

Chuck has been writing about Lehigh football since the dawn of the internet, or perhaps it only seems like it. He’s executive editor of the College Sports Journal and has also written a book, The Rivalry: How Two Schools Started the Most Played College Football Series.

Reach him at: this email or click below: