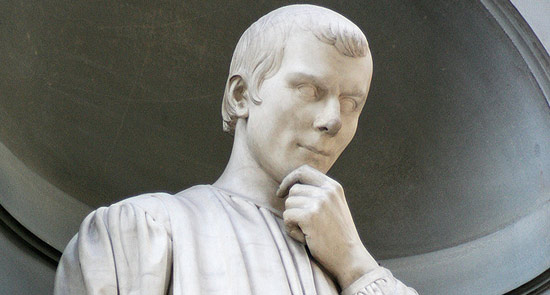

Machiavelli Would Love the Power 5’s Latest Scheduling Play

By Chuck Burton

Publisher/Managing Editor

College Sports Journal

PHILADELPHIA, PA. — The College Football Playoff selection committee met last week at the Four Seasons Hotel Resort of Dallas to try to figure out a puzzle that has stumped college football writers for the past one hundred years.

“How the heck are we going to determine the top four teams in the country?”

The end result of the meetings didn’t result in a heck of a lot to illuminate the issue as to how “schedule strength” was going to be factored into the playoff committee’s calculus.

“Every game that everybody plays will be taking into consideration,” Bill Hancock said, which didn’t clarify anything. “To the committee it won’t matter whether you played an eight- or nine-game conference schedule. But it will matter who you played for your 12 or 13 games. And, of course, how you did against them.”

The trouble is that evaluating the relative strength of “who you played for your 12 or 13 games” is a skill nobody has mastered over the past 100 years.

What is clear, though, is that the schools from the so-called “Power 5” conferences know how to get “schedule strength” in such a way that will effectively prevent any member of the other conferences to compete in the playoff: Schedule more conference games, and schedule more games against other “Power 5” schools.

It’s a Machiavellian move.

Take one moment to contemplate the thankless, impossible job that the members of the College Football Playoff committee will have.

They cannot watch every single minute of every college football game played during the course of the regular season, which would be the data required to truly, objectively judge the relative worth of all 128 Bowl Subdivision teams.

Instead they, like every other college football fan in America, will rely on ESPN, Fox, CBS, their local news, and websites all over the country to get an edited-down package of highlights of the games that they weren’t able to watch in their entirety.

Are they going to spend a lot of time evaluating the relative merits of, say, a 4-8 West Virginia team as they would 11-1 Baylor?

Common sense would dictate “no”, but to determine the relative worth of a Bear win over the Mountaineers versus that of other teams, you’d theoretically need to say “yes” – if you’re really trying to be completely fair in determining the worth of their schedule.

Ideally, each team Baylor played and the other teams they would be up against would have their games equally scrutinized, meticulously watching every minute of their games, judging their wins and losses, any “style points” you’d want to add into the mix (is a 73-42 win different than a 30-6 win, or a 12-6 win?), and any other criteria the CFP members would want to use as information.

Take, for example, trying to pick a hypothetical playoff field from last year’s field.

Picking 13-0 Florida State as the ACC champion was a no-brainer, and perhaps 12-1 Auburn as the winners of the SEC, but picking the last two spots would have been anything but easy.

Eight other teams finished with only one regular-season loss: Northern Illinois (12-1), Alabama (11-1), Louisville (11-1), Michigan State (12-1), Fresno State (11-1), Baylor (11-1), Central Florida (11-1), and Ohio State (12-1).

Additionally, Stanford (11-2) would have merited consideration due to the fact they won the Pac-12 and beat a boatload of ranked teams.

So, how to pick those last two teams?

They could only consider those teams that were conference champions, which would include two-loss Stanford, Baylor, Michigan State, and perhaps UCF.

But that would exclude 11-1 Alabama and 11-1 Ohio State, which were ranked No. 3 and No. 7 in the final AP Top 25 poll before the bowls.

Imagine for a second two-loss Stanford making the playoffs over an 11-1 Alabama team that was ranked ahead of them in the AP Top 25 poll at No. 3. And then imagine the appearance of conflict of interest when people discovered that Condoleezza Rice, Stanford’s provost, was on the committee to choose the teams.

“Members of the 13-person committee would recuse themselves from discussions of teams where they’ve had a previous or current financial commitment, though the exact degrees of separation are unclear,” a CBS Sports article stated recently about the CFP’s recusal policy.

It’s inevitable that this policy will ultimately be under massive scrutiny at some point in the future. If four teams were to have been picked last season by this committee, it absolutely would have been.

The CFP can come up with whatever recusal rules they wish, but no amount of defined protocol saying that Rice can’t be in the room when they make the decision will sway the Twitterverse that a conspiracy was afoot to put Stanford in.

So let’s say, to avoid criticism, instead they look at data, like Top 25 polls and computer rankings, more than they do conference championships.

This is where the evil genius of the Power 5’s scheduling policies really kicks in.

When computing “schedule strength”, the entirety of a school’s opponents are evaluated. In a 12- or 13- game schedule, the great majority of those games are going to be conference games.

That means that membership in a particular conference plays an outsized role in determining “schedule strength”. Think of it this way: of a typical 12 game FBS schedule, 2/3rds of those games will be against conference foes.

For example, in 2014 Vanderbilt plays Temple, UMass, Old Dominion, and Charleston Southern, an FCS school, out-of-conference.

With two squads that went a combined 3-21 in FBS play, a Monarch team only two years removed from FCS, and a lower-level FCS school, you’d think that Vanderbilt’s “schedule strength” would be horrible.

But through an accident of history, Vandy plays in the SEC, where they play Georgia, Florida, Missouri, and other SEC teams that are likely to be in the Top 25 or better.

If they go undefeated, they’ll be able to compete against the other SEC divisional champion, like Alabama, Auburn, or LSU.

So if it comes to the selection committee, Vandy will have the “schedule strength” to qualify for the playoff – completely thanks to its SEC schedule.

In the “schedule strength” game, proximity to “strong” schools counts just as much as playing them. If Kentucky beats LSU in a once-in-a-lifetime win, then Vanderbilt beats Kentucky, Vanderbilt gets “schedule strength” even though they didn’t line up against LSU.

It’s this proximity which really puts the heat on FBS schools that are not a part of the “Power 5”.

Schools like Vanderbilt can simply count on some team in their conference to carry the “schedule strength” weight, and can schedule cupcakes outside the conference to get wins. But schools like UCF need to schedule aggressively out-of-conference, win all those games, and then power through their conference schedule to hope to qualify.

But now the “Power 5” are pledging to schedule one out-of-conference game to other “Power 5” schools, thus robbing the “Non-Power 5” schools of a critical game playing against a school with proximity to the top squads.

Vanderbilt already has at least 2/3rds of its schedule with proximity to top teams, or 8 out of 12 conference games. With the mandatory scheduling, it becomes 3/4ers of the schedule, or 9 of their 12 games.

That directly translates to one less chance to give non-Power 5 teams “schedule strength”, and if the chances were remote that a non-Power 5 team would make the playoff before, with the new agreement between the Power 5 conferences it just reached shoot-the-moon territory.

And it’s not like the schools have much control over the overall “schedule strength” going into the season.

FBS schedules are set well before the season is contested, with only 1/3 of the overall schedule to add out-of-conference opportunities to add “strength” to the conference slate.

When the schools’ athletic directors make the schedules, they make educated guesses as to where their opponents would be at the end of the season – but that’s all they are.

Schedule strength is generally determined, before the season, by the athletic director’s preconceived notion as to who the great teams will be in the future. Then the season actually plays itself out, and the athletic directors discover whether they were correct or not.

Now, those opportunities will be reduced.

The extremely remote chance of playoff eligibility for a non-Power 5 school, increasingly, will hinge on hitting a quadrifecta of power-conference teams that are either members of the Top 25, or teams that are damned close, then sweeping through their regular-season schedule.

There can’t afford to be slip-ups – even a close win on the road somewhere will be under huge scrutiny.

And it seems like the Power 5’s scheduling decisions, paradoxically, will most affect non-Power-5 schedules.

It seems like those teams will need to drop some FCS games in order to have a slim chance at the playoffs, because non-Power 5 schools will need to redouble their efforts to get FBS games, even, perhaps, in one-and-done scenarios, not insisting on playing return games at home.

This, of course, serves the Power 5 conferences well.

Non-Power 5 schools will now demand less in terms of guarantees for games, because they’ll need the games more to be at all relevant. The price of guarantees levels off, or perhaps drops.

That adds to Power 5 teams’ bottom lines, because after all, college sports is a business, right?

Reducing access to the extremely lucrative playoff, tilting the game of guarantees away from market forces by purposefully limiting the number of contests against non-Power 5 schools and FCS schools – it’s a scheduling move Machiavelli would have loved.