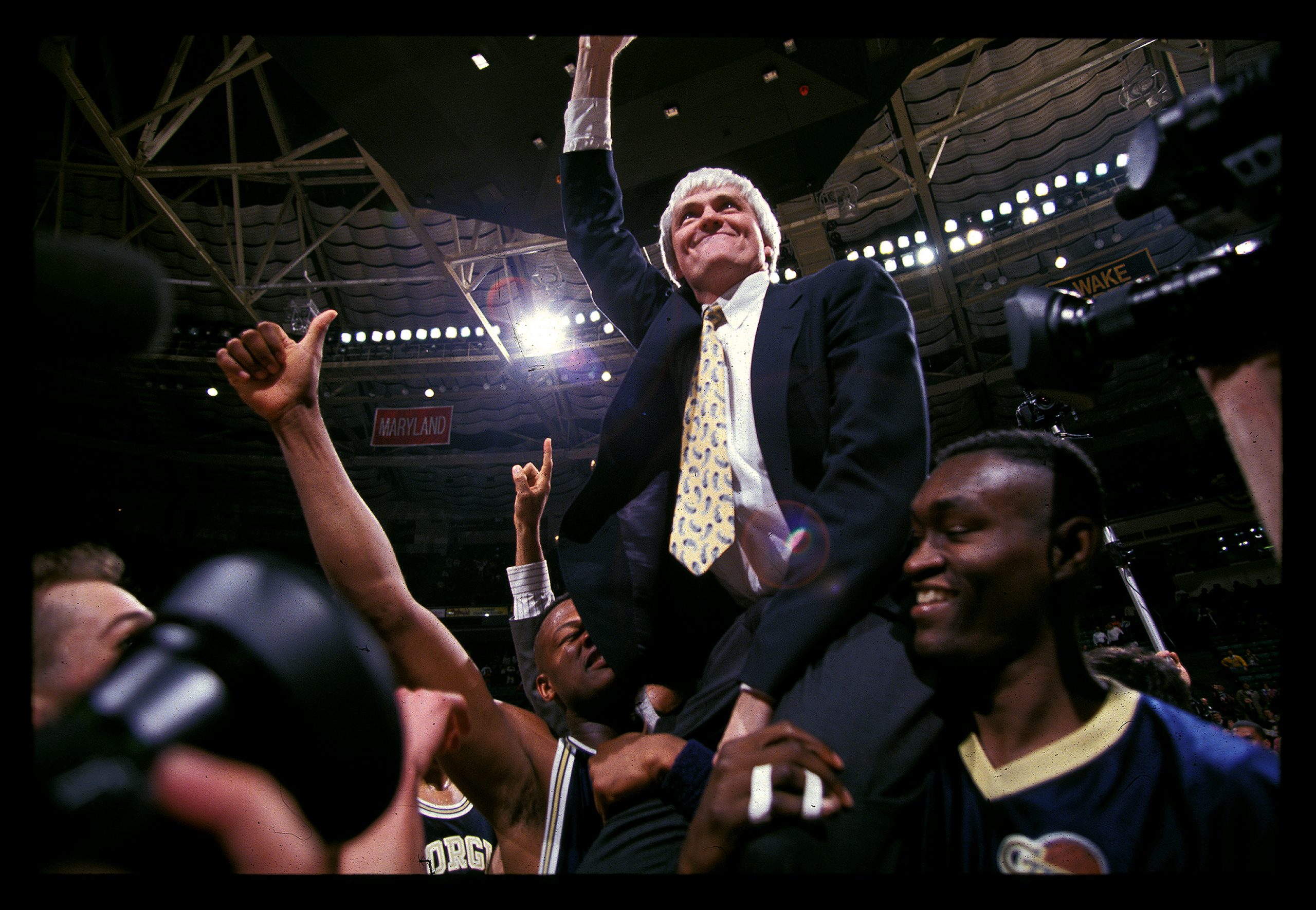

Former Georgia Tech Head Basketball Coach Bobby Cremins Lives Out Dream

HILTON HEAD, S.C. – The platinum blond hair made Bobby Cremins one of the most easily recognizable figures in college basketball. The success he had in turning collegiate basketball programs around made him one of the best coaches in the history of the game.

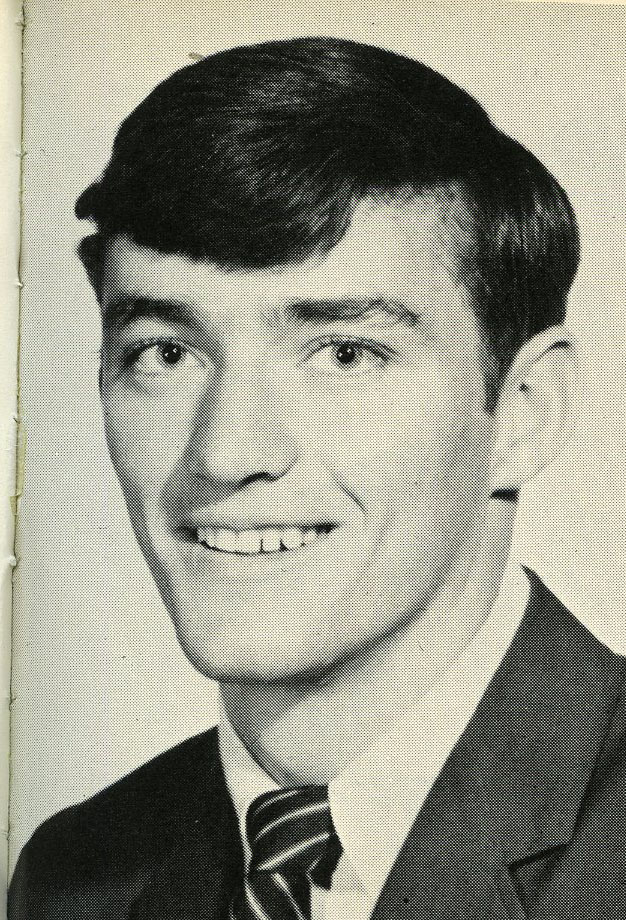

Cremins, the son of Irish immigrants, grew up in the Bronx, N.Y. and knew from an early age that basketball is what he wanted to spend his life being a part of and leaving his mark on the sport.

“Like all the kids in the neighborhood, I played a lot of stickball and basketball,’ said Cremins, who lived across the street from an asphalt basketball court that resembled many others that dotted the New York City landscape and helped make the city a mecca of basketball talent of the time that continues today. “I could walk out my front door and the first thing I would see was the basketball court across the street and I quickly gravitated more and more to the game and I was finding that every day of my life my passion for the game was growing.”

The budding basketball player began his career by trying out for his grammar school team where he rubbed shoulders for the first time with a legendary coach who would help fuel his passion for the game. Jack Lyons, who coached baseball at Fordham, spent two days a week teaching Cremins and the other young hopefuls the fundamentals of the game at St. Anthanasius Grammar School.

“I don’t think the Fathers paid (Lyons) … they just gave him a lot of blessings,” quipped Cremins, who would go on to start for his team.

The success he had in those early years under Lyons opened the door for some tryouts with local high school teams in New York’s tradition-rich Catholic School League, which offered scholarships to many deserving players of the time. Cremins had several tryouts, including one at Power Memorial where a young Lew Alcindor also had a tryout that same year before playing at the school and later becoming one of the greatest players in basketball history.

Cremins would eventually get a scholarship to play at All Hallows High School, located in the shadows of Yankee Stadium. He transferred to Frederick Military Academy, in Portsmouth, Va., for his final year of high school to concentrate on improving his grades.

It was there that Cremins caught the eye of a South Carolina assistant coach who was at a game against Frederick Military Academy scouting a teammate of Cremins.

Cremins scored 27 points in the game that night causing the coach to ask Cremins about possibly enrolling to play basketball at South Carolina, which was coached by Frank McGuire.

He was well aware of McGuire and his record of success as a college coach which began in New York City when he guided St. John’s to a 102-36 (.739) record in five seasons (1947-52) before becoming coach at North Carolina and establishing UNC as a basketball powerhouse.

McGuire led the Tar Heels to a 164-58 (.739) overall record in nine seasons (1952-61). His 1956-57 team finished the year 32-0 and defeated Kansas 54-53 in triple overtime to win the national championship. McGuire’s team also needed triple overtime to defeat Michigan State 54-50 in the national semifinal round.

“(McGuire) was a legend,” Cremins said. “I knew he had played baseball and basketball at St. John’s and I knew he had won the national title while at North Carolina … and he won it with five New York City area guys.

“Frank McGuire became like a godfather to me,” Cremins added.

Cremins fit in nicely at South Carolina in McGuire’s system. A 6-foot, three-inch guard, Cremins would go on to play in 77 games during his collegiate career. He finished with 589 points (7.6 ppg) as a Gamecock and helped his team to a 61-17 overall record in his three seasons.

His career was not void of setbacks, such as the 1969-70 season. A season Cremins labels as “Crisis No. 1.”

After easily defeating Auburn 84-63 in the season opener, Cremins and the Gamecocks came out on the short end of a 55-54 decision to Tennessee in the next game. But the team rebounded in a big way and reeled off wins in each of the next 17 games to improve to 18-1 on the season.

Davidson ended that streak with a 68-62 win over South Carolina which would eventually win the Atlantic Coast Conference regular season title with a perfect 14-0 record.

With sights set on playing in the NCAA Tournament the Gamecocks got past Clemson (34-33) and Wake Forest (79-63) to advance to the ACC championship game. Cremins and his team came out on the wrong end of a 42-39 overtime decision to N.C. State to end USC’s season.

The NCAA Tournament only invited 25 teams that season and N.C. State’s win in the ACC title game made the Wolfpack the only ACC team to make the tournament field.

“The way our season ended was a really rough time for me,” Cremins said. “We had such a great team. We went undefeated in the ACC and here we were 25-3 on the year after losing that game … and we had nowhere to go.”

Like all players Cremins dreamed of playing professionally following his graduation from South Carolina in 1970. His career was short lived as he played one year as a pro in Ecuador before embarking on his coaching career.

“I always wanted to play pro ball,” Cremins said, “that was the first goal.

“But when the playing door closed, the coaching door opened,” he added.

Cremins wasted little time in kicking that door open wide.

COLLEGE COACHING

Cremins returned from Ecuador and became an assistant coach at Point Park College in Pittsburgh for the 1971-72 season. He returned to South Carolina the following year as an assistant to McGuire with the Gamecocks. He spent the first year back in Columbia as a graduate assistant and became a full-time assistant for the next five seasons before becoming a head coach for the first time at the age of 27 by taking over at Appalachian State.

Cremins inherited a program that had won just 22 games since joining Division 1 five years earlier and had come off the worst record in school history by going 3-23 the year before Cremins’ arrival in Boone.

After recording a 13-14 record in his first season the Mountaineers compiled an 87-56 record over the next five seasons and won the Southern Conference regular season championships. His 1978-79 team swept the regular season and conference tournament title and advanced to the NCAA Tournament.

His tenure at the school ended following the 1980-81 season in which the Mountaineers finished 20-9. Cremins was 100-70 in his six seasons (1975-81) at the school.

GEORGIA TECH

With his name becoming known across the college basketball landscape because of his success at Appalachian State Cremins sought to achieve another goal he had set for himself more than a decade earlier.

“My goal was to become a head coach in the ACC and to win a championship,” Cremins admits.

He applied for openings at Duke and at North Carolina State. He was bypassed for those by Mike Krzyzewski and Jim Valvano, respectively, who were hired by those schools in 1980.

Cremins fulfilled part of his wish the following year when he took over a struggling Georgia Tech program that posted just one winning season over the past decade and suffered the worst season in school history the previous season when the Yellow Jackets finished 4-23 and going winless in conference play.

And like at his previous stop the success at Georgia Tech was quick to develop.

In just his third year in Atlanta he guided the Yellow Jackets to the 1984 NIT to give Tech its first postseason berth of any kind in 13 years.

The goal of a championship was reached the next year as Tech earned a share of the ACC regular season championship.

The winning continued and in 1990 Cremins and Georgia Tech once again shared the ACC regular season title and knocked off in the ACC tournament championship. The Ramblin’ Wreck advanced all the way to the Final Four by slipping past Minnesota 93-91 in the Southeast Regional championship game in New Orleans.

That’s when they Jackets hit a snag. They lost in the national semifinal 90-81 to UNLV which went on to win the title two days later by trouncing Duke 103-73 in the championship game at McNichols Arena in Denver.

The Yellow Jackets finished the season with a 28-7 record and Cremins was voted the Naismith College Coach of the year. Those 28 wins remain a school record more than a quarter century after achieving that lofty mark.

Cremins’ success was obviously not his alone.

He also proved to be a master at recruiting.

Cremins has coached some of the best players in college basketball history. Names like Mark Price (Cleveland Cavaliers) and John Salley (Detroit Pistons) would play for Cremins during his early tenure at Georgia Tech and helped set the table for the future success of the program in Atlanta.

Dennis Scott, Kenny Anderson, Jon Barry and Travis Best also donned the colors of the Yellow Jackets under Cremins’ tutelage.

“We were fortunate to recruit some incredibly talented players who also excelled at being great people above all else,” Cremins said.

While the success at turning around the Tech program helped solidify Cremins’ coaching legacy, a 1993 incident will forever be linked to Cremins.

After leading Tech to a 19-11 season in 1992-93 he agreed to return to his alma mater and coach South Carolina. Cremins changed his mind just three days and decided to remain at Georgia Tech.

“That would have to be considered Crisis No. 2 or 3,” he said of the stunning turn of events. “I have great memories of my time at South Carolina and learning from one of the greatest coaches in the history of the game,” he said. “But, we had also done some great things at building a culture of success and in the end it was just not the right time to leave Tech.”

Cremins, who was voted ACC coach of the year three times during his time at Tech, retired following the 1999-2000 season after 19 seasons at Georgia Tech.

“We started struggling a bit toward the end of my time there,” said Cremins, whose team managed a just a 47-48 record during that span.

“My game plan was to sit out a year or two and get back into coaching,” said Cremins, who compiled a 354-237 (.599) record in his 19 seasons leading the Yellow Jackets and his team made 10 appearances in the NCAA tournament during his time at the school.

His 354 wins are by far the most in Georgia Tech history.

COLLEGE of CHARLESTON

Cremins’ time away from the game last a little longer than he expected. After rejecting numerous opportunities to return to coaching and touring the country delivering motivational speeches he finally did not return to coaching until taking over at the College of Charleston in 2006.

That move held a bit of irony when Greg Marshall had agreed to become coach at the school but reversed his decision a few days later like Cremins had done more than a decade earlier at Georgia Tech. Marshall went on to coach at Wichita State.

Cremins spent nearly six full seasons at the school and guided his teams to a 125-68 record. Citing medical issues he took a leave of absence midway through the season and did not return. He retired from coaching at the end of the 2011-12 season.

“Things were just not as balanced in my life as they should have been and needed to be,” he said. “I was simply burned out.”

Cremins’ overall coaching record stands at 579-375 (.607) in 25 years.

LATER LIFE

Cremins, who served as an assistant coach for the U.S. team that won a gold medal at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, remains active in basketball and gets together with former players whenever the opportunity arises.

He also looks back on his brilliant coaching career.

“We had a great run,” the iconic coach said. “We built things that no one thought we would be capable of building and that was because we all bought in to the same vision of successful at doing things the right way.”

He also beams with pride in his achievements from the rough streets of New York.

“I loved doing what I did,” he said. “My parents moved here for a better life and I like to think I fulfilled part of their dream in building a better life.”

Always the inspiration, Cremins, who now lives in Hilton Head, S.C., said young players need not be afraid of setbacks as they work to develop their games.

“It can be hard to deal with things when they don’t go the way we have planned,” he said. “Setbacks can cause confusion and uncertainty, but if we stick with the plan and listen to the people we are working together with to improve, things will come to fruition.”

A native of Bismarck, N.D., Ray is a graduate of North Dakota State University where he began studying athletic training and served as a student trainer for several Bison teams including swimming, wrestling and baseball and was a trainer at the 1979 NCAA national track and field championship meet at the University of Illinois. Ray later worked in the sports information office at NDSU. Following his graduation from NDSU he spent five years in the sports information office at Missouri Western State University and one year in the sports information at Georgia Tech. He has nearly 40 years of writing experience as a sports editor at several newspapers and has received numerous awards for his writing over the years. A noted sports historian, Ray is currently an assistant editor at Amateur Wrestling News.