Lawyers in O’Bannon Trial Would Be Wise To Look At College Football History

By Chuck Burton

Publisher/Managing Editor

College Sports Journal

PHILADELPHIA, PA. — It’s been billed as the trial that might break up the NCAA.

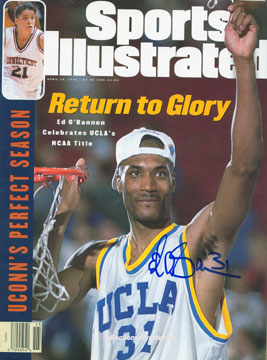

The O’Bannon trial, involving the former UCLA basketball standout Ed O’Bannon, asks questions of whether the name, image or likeness of college players when they played college ball is owned by the NCAA.

It is certainly a landmark case, no matter how U.S. district judge Claudia Wilken judges it.

But as ever, some of the talk during the trial betrays a lack of understanding of the collegiate landscape long ago.

In a line of questioning, Wilken asked Glenn Pomerantz, the lawyer representing the NCAA, whether “the NCAA is so sure college fans would lose interest if student-athletes were compensated,” Sports Illisutrated’s Mike McCann reported.

“Pomerantz responded by noting that before 1905, college sports fandom was muted as colleges had professional and amateur athletes playing alongside one another,” McCann continued.

At Lehigh, Lafayette and Princeton, at least, this can be proved fairly easily to not be the case – though it probably reveals things that both sides of the O’Bannon case would rather you not know.

In the 1890s, football in the horse and buggy era was becoming big business.

When you look at literature from around this time from Lehigh and Lafayette, you see college presidents and historians starting to note how huge college football was becoming.

In 1893, the Yale/Princeton game generated $30,000 and had an attendance of 25,194 fans, according to the New York Times.

To put this in perspective, both Yale and Princeton, from a single game, split the value of more than $750,000 in today’s money.

Schools like Lehigh and Lafayette were looking at the success of nearby Princeton and were eager to get into the game. In fact some of the first “guarantees” were spent by big-times schools like Princeton in order to get home games, and to guarantee that the other side would actually show up.

More to the point, though, there were starting to be some serious questions about amateurism – and transfers.

In the 1890s, there were no rules stating that students had to be undergraduates. In fact, the University of Pennsylvania were notorious for enrolling non-students for the sole purpose of playing football.

“There were on the opposing team three graduates, two of whom were married men and none who were on the rolls of the college or in any way connected with it,” Lehigh’s student newspaper said in 1889 about a matchup with them.

That’s not to say Lehigh was any better than UPenn in some regards. Two of Lehigh’s best players of that era were Paul Dashiell and D.M. Balliet, both whom came to Lehigh in their early 20s.

In fact, Balliet was playing football for Lehigh in 1891 at the age of 24, when he decided the follwoing year to transfer to Princeton in order to compete for a national championship with the Tigers.

Again, no rules were in place to prevent these types of things from happening, but it meant that in 1892, Balliet would be suiting up against the same players he called teammates the prior year.

Lafayette, Lehigh’s old rival, also had their share of hired guns. In 1896, 25 year old Fielding Yost competed against Lafayette as a member of the university of West Virginia. A couple of weeks later after Lafayette’s victory over the Mountaineers, he suited up for the Maroon and White against Penn, where Lafayette defeated them.

It’s also worth mentioning that having star players in their mid-20s would have been an enormous advantage, who would have been bigger and more skilled than undergraduates just learning the game.

By the late 1890s, faculty at the schools themselves were starting to get tired of the antics of Penn, Princeton and other schools bringing in players that in no way represented their student bodies.

It even led to the breakup of the old football order and caused the birth of other collegiate organizations with the specific purpose of changing the rules to prevent situations like these.

Which brings us back to the present day.

In the O’Bannon case, trying to argue that college sports were any less popular then than today seems ridiculous.

Football, whose highest level at that time was the college level, was wildly popular and took up large portions of real estate in the papers at the time.

But revisiting the 1890s also shows the critical need for a competent rule-making body that prevents students and athletic departments from their worst excesses.

If we were to go back to the nonexistent or ineffective enforcement of rules today, it’s not all that much of a stretch to see ourselves back to the relative lawlessness of the antics of schools in the 1890s.

The main arguments for amateurism in the 1890s were not about compensation, but basically ones of fairness. Bringing in players in their mid-20s to just play football put some schools at a disadvantage, and the schools who valued that principle forced the hands of those that did not.

It also ensured that larger-resourced schools were not able to simply purchase the best players, as the best players were invariably older and more physically developed than undergraduates.

Judge Wilken ought to think about how the aftermath of the “name-image-likeness” trial could force, effectively, two types of collegiate sport: one with the extra resources of “name-image-likeness”, and one without.

Amateurism in the 1890s was defined not as a way to keep student-athletes down, but as an attempt at a fair method of making sure everyone was playing under the same rules.

College sport has evolved into something that could not have been conceived in the 1890s. But that doesn’t mean that the 1890s don’t offer valuable lessons for the trials of today.